At many churches, at some private houses, but also in museums, there are stone testimonies of Styria’s Roman past. These so-called Roman stones contain not only text, but often also images, such as scenes from ancient sagas or portraits.

In Styria the occupation with Roman stones has a very long tradition. As early as 1506, Emperor Maximilian I had inscription stones from Flavia Solva and Celeia (Celje) brought to Graz so that they could be displayed for all to see at Graz Castle.

The scientific research of Roman stones has also been a Styrian tradition since Erna Diez began collecting all Roman stones according to art-historical aspects in the 1940s. This tradition has since been firmly anchored at the University of Graz and the Joanneum Universal Museum.

Among the inscription stones, besides the dedicatory inscriptions and the very frequent funerary inscriptions, the milestones and the honorary inscriptions for Roman emperors are particularly noteworthy, as they show us the connections and contacts within the Roman Empire.

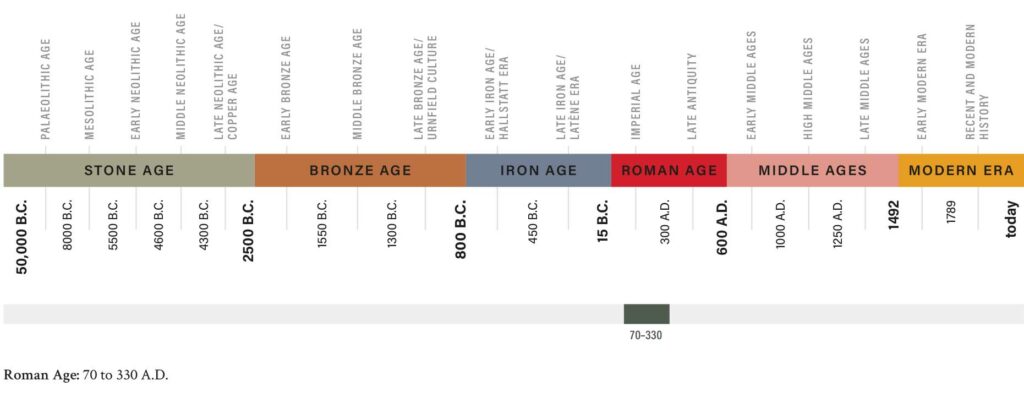

For example, the governor of Noricum mediterraneum donated an honorary inscription to the Emperor Constantine (306-337) around 330 A.D., the occasion of which we no longer know (fig. 1). Milestones served as orientation for travelers, indicating the distance to the next destination. Today they help us to trace Roman road courses, for example the two milestones from the Kugelstein, which were found 40 Roman miles upstream from Flavia Solva and are thus evidence of a Roman road through the Mur river valley.

Consecration inscriptions were often placed on altar-shaped stones and erected in those sanctuaries by whose deity a wish had been granted. Aurelius Celsinus had apparently promised Iupiter Uxlemitanus, a deity with pre-Roman roots, a dedication altar for his son’s happy return home from military service. Upon his return, he redeemed the vow (fig. 2).

By far the largest quantity among the Roman stones in Styria, almost 80%, are the remains of funerary monuments. In addition to the numerous grave inscriptions, these also include parts of buildings which, similar to chapels, stood at the wayside, and portraits of the deceased. These portraits are a particularly important source for the Roman period in Styria, since the deceased were portrayed in special clothing, or gave clues to professions or personal preferences by means of the objects they held in their hands. Recently, it has also been considered whether gestures could have a special meaning. One of the best known examples of funerary portraits is the medallion of a scribe from Flavia Solva, who was depicted holding a writing tablet and a stylus (fig. 3).

Since no troops were stationed in Styria during the Roman period, Roman stones of military personnel are of particular interest. The majority are from veterans who had served in legions in neighboring Pannonia. One centurion, whose name we do not know, had his portrait painted with all the decorations of his rank (fig. 4).

From the names mentioned in the inscriptions various information can be deduced: On the one hand, in addition to typical Roman three-part names along the lines of “Gaius Iulius Caesar,” we also find Romanized pre-Roman and even Greek names; on the other hand, the names also express the status. In addition to Roman citizens and slaves – who in rare cases also had the means to have funerary monuments erected – there were also free citizens without civil rights.

The rescript of October 14, 205 A.D., which was probably addressed to the governor of the province of Noricum, occupies a special position. In it, the emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) confirms the privileges of 93 persons in seven columns, the members of the “collegium centonariorum.” The so-called “fire brigade inscription” was found in 1915 during excavations of the Joanneum.

Text: Mag.a Dr.in Barbara Porod